The following article contains excerpts from Lieutenant General Robert P. Ashley, Jr.’s, preface to, as well as the report itself, authored by the Defense Intelligence Agency’s (DIA) and are republished with permission of the DIA...

“Chinese leaders characterize China’s long-term military modernization program as essential to achieving great power status. Indeed, China is building a robust, lethal force with capabilities spanning the air, maritime, space and information domains which will enable China to impose its will in the region. As it continues to grow in strength and confidence, our nation’s leaders will face a China insistent on having a greater voice in global interactions, which at times may be antithetical to U.S. interests.

“With a deeper understanding of the military might behind Chinese economic and diplomatic efforts, we can provide our own national political, economic, and military leaders the widest range of options for choosing when to counter, when to encourage, and when to join with China in actions around the world.

“This report offers insights into the modernization of Chinese military power as it reforms from a defensive, inflexible ground-based force charged with domestic and peripheral security responsibilities to a joint, highly agile, expeditionary, and power-projecting arm of Chinese foreign policy that engages in military diplomacy and operations across the globe.”

Space/Counterspace

Outer space has become a commanding height in international strategic competition. Countries concerned are developing their space forces and instruments, and the first signs of weaponization of outer space have appeared. China has all along advocated the peaceful use of outer space, opposed the weaponization of and arms race in outer space, and taken an active part in international space cooperation. China will keep abreast of the dynamics of outer space, deal with security threats and challenges in that domain, and secure its space assets to serve its national economic and social development, and maintain outer space security. — Excerpt from China’s Military Strategy, May, 2015

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) historically has managed China’s space program and continues to invest in improving China’s capabilities in space-based ISR, satellite communication, satellite navigation, and meteorology, as well as human spaceflight and robotic

space exploration.1

China uses its on-orbit and ground-based assets to support national civil, economic, political, and military goals and objectives.

Strategists in the PLA regard the ability to use space-based systems and deny them to adversaries as central to enabling modern, informatized warfare.

As a result, the PLA continues to strengthen its military space capabilities despite its public stance against the militarization of space.

Space operations probably will form an integral component of other PLA campaigns and serve a key role in enabling actions to counter third-party intervention during military conflicts.

China continues to develop a variety of counterspace capabilities designed to limit or prevent an adversary’s use of space-based assets during crisis or conflict. In addition to the research and possible development of satellite jammers and directed-energy weapons, China has probably made progress on kinetic energy weapons, including the anti-satellite missile system tested in July 2014.2

China is employing more sophisticated satellite operations and probably is testing on-orbit dual-use technologies that could be applied to counterspace missions. The PLA’s Strategic Support Force (SSF), established in December OF 2015, has an important role in the management of China’s aerospace warfare capabilities.3

Consolidating the PLA’s space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities into the SSF enables cross-domain synergy in “strategic frontiers.” The SSF may also be responsible for research, development, testing, and fielding of certain “new concept” weapons, such as directed energy and kinetic energy weapons.

The SSF’s space function is primarily focused on satellite launch and operation to support PLA reconnaissance, navigation, and communication requirements. [For more on the SSF, please see Appendix E.]

Space and counterspace capabilities — such as missile forces, advanced air and seapower, and cyber capabilities — are critical for China to fight and win modern military engagements.

To support various requirements, China has built a vast ground and maritime infrastructure enabling spacecraft and space launch vehicle (SLV) manufacture, launch, C2, and data downlink.

— Satellites —

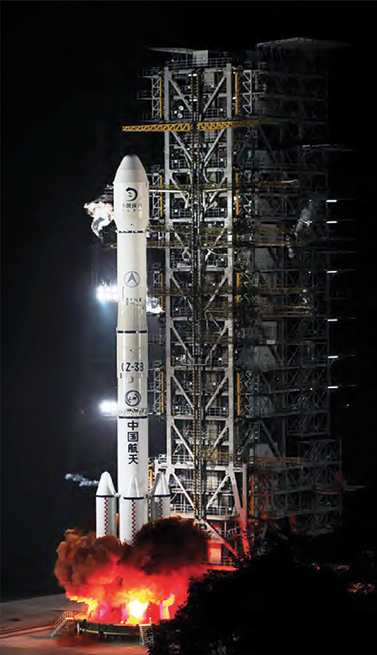

Long March-3B SLV in midlaunch. Photo is

courtesy of AFP.

China employs a robust space-based ISR capability designed to enhance its worldwide situational awareness. Used for civil and military remote sensing and mapping, terrestrial and maritime surveillance, and military intelligence collection, China’s ISR satellites are capable of providing electro-optical (EO) and synthetic aperture radar imagery, as well as electronic intelligence and signals intelligence data.4

China pursues parallel programs for military and commercial communications satellites (COMSATs), and owns and operates about 30 COMSATs that are used for civil, commercial, and military satellite communications. The PLA operates a small number of dedicated military COMSATs.5

China’s civil COMSATs incorporate turnkey off-the-shelf, commercially manufactured components and China produces its military-dedicated satellites domestically.6

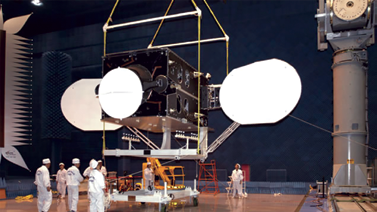

China continues to launch new COMSATs to replace its aging satellites and increase its overall satellite communications bandwidth, capacity, availability, and reliability. China uses its domestically produced Dongfanghong- 4 (DFH-4) satellite bus—the structure that contains the components of the satellite— for its military COMSATs.7

Even though early satellites suffered mission-ending or mission-degrading failures, the DFH-4 has become a reliable satellite bus. The PLA and government continue to vigorously support the program and have signed numerous contracts with domestic and international customers for future DFH-4 COMSATs.

A Chinese Space Operations Center. Photo is courtesy of AFP.

The DFH-4 bus has also allowed China to position itself as a competitor in the international COMSAT market, orchestrating many contracts with foreign countries to supply on-orbit satellites, ground-control systems, and training.

In 2008, China launched the first Tianlian data-relay satellite of its China Tracking and Data Relay Satellite constellation. As of December 2017, China had four Tianlian data-relay satellites on orbit, allowing China to relay commands and data to and from its satellites even when those satellites were not over Chinese territory.

In 2000, China launched its first Beidou satellites to test the development of a regional satellite navigation system. By 2012, China had established a regional satellite navigation constellation consisting of 10 Beidou satellites and had initiated testing of a global constellation similar to the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS).8

As Beidou satellites continue to be placed in orbit, by 2020 China will complete its global constellation of 27 Beidou satellites while maintaining a separate regional constellation providing redundant coverage over Asia.9

Photo of China’s Dongfanghong- 4 (DFH-4) satellite bus. Image is

courtesy of CAST.

China owns and operates 10 domestically produced Fengyun and Yunhai meteorological satellites.10 The China Meteorological Administration supports civilian and military customers with the delivery of meteorological data and detailed weather forecasts. The newer satellites house almost a dozen all-weather sensors concerning atmospheric conditions as well as maritime terrain data for military and civilian customers. China’s membership in the World Meteorological Organization grants it free access to global meteorological data from the international organization’s 191 members.11

— Counterspace —

The PLA is acquiring a range of technologies to improve China’s counterspace capabilities. China is developing anti-satellite capabilities, including research and possible development of directed-energy weapons and satellite jammers, and probably has made progress on the anti-satellite missile system that it tested in July 2014. China is employing more sophisticated satellite operations and probably is testing dual-use technologies that could be applied to counterspace missions.12

China has not publicly acknowledged the existence of any new programs since it confirmed it used an anti-satellite missile to destroy a weather satellite in 2007. PLA writings emphasize the necessity of “destroying, damaging, and interfering with the enemy’s reconnaissance… and communications satellites,” suggesting that such systems, as well as navigation and early warning satellites, could be among the targets of attacks designed to “blind and deafen the enemy.”13,14

Artistic rendition of a Chinese Beidou

satellite. Image is courtesy of CAST.

— Human Spaceflight + Space-Exploration Probes —

China became the third country to achieve independent human spaceflight in 2003, when it successfully orbited the crewed Shenzhou-5 spacecraft, followed by space laboratory Tiangong- 1 and -2 launches in 2011 and 2016, respectively. China intends to assemble and operate a permanently inhabited, modular space station capable of hosting foreign payloads and astronauts by 2022.15

China is the third country to have soft-landed a rover on the Moon, deploying the rover Yutu as part of the Chang’e-3 mission in 2013. China’s Lunar Exploration Program plans to launch the first mission to land a rover on the lunar far side in 2018 (Chang’e-4), followed by its first lunar sample-return mission in 2019 (Chang’e-5).16,17,18

— Space Launch —

Artistic rendition of China’s Fengyun

satellite.

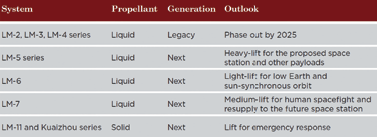

China has a robust fleet of launch vehicles to support its requirements. The Chang Zheng, or Long March, and Kuaizhou SLVs can launch Chinese spacecraft to any orbit.

— Cyberspace —

Authoritative PLA writings identify controlling the “information domain”—sometimes referred to as “information dominance”—as a prerequisite for achieving victory in a modern war and as essential for countering outside intervention in a conflict.22

The PLA’s broader concept of the information domain and of information operations encompasses the network, electromagnetic, psychological, and intelligence domains, with the “network domain” and corresponding “network warfare” roughly analogous to the current U.S. concept of the cyber domain and cyberwarfare.23

The PLA Strategic Support Force (SSF) may be the first step in the development of a cyberforce by combining cyber reconnaissance, cyberattack, and cyberdefense capabilities into one organization to reduce bureaucratic hurdles and centralize command and control of PLA cyber units.

Artistic rendition of China’s Tiangong-2

space lab docked with a crewed Shenzhou

spacecraft. Image is courtesy of China

Aerospace Science and Technology

Corporation (CAST).

Official pronouncements offer limited details on the organization’s makeup or mission. China’s President Xi simply said during the SSF founding ceremony on December 31, 2015, that the SSF is a “new-type combat force to maintain national security and [is] an important growth point for the PLA’s combat capabilities.”24

The SSF probably was formed to consolidate cyber elements of the former PLA General Staff Third (Technical Reconnaissance) and Fourth (Electronic Countermeasures and Radar) Departments and Informatization Department.25,26

Cyberspace has become a new pillar of economic and social development, and a new domain of national security. As international strategic competition in cyberspace has been turning increasingly fiercer, quite a few countries are developing their cyber military forces.

Being one of the major victims of hacker attacks, China is confronted with grave security threats to its cyber infrastructure. As cyberspace weighs more in military security, China will expedite the development of a cyberforce, and enhance its capabilities of cyberspace situation awareness, cyber defense, support for the country’s endeavors in cyberspace and participation in international cyber cooperation, so as to stem major cyber crises, ensure national network and information security, and maintain national security and social stability. — Excerpt from China’s Military Strategy, May, 2015

China’s space launch sites. Image source: DIA, D3 Design. All locations are approximate. Boundary representation is not necessarily authoratative.

Depiction of claims on this map is without prejudice to U.S. non-recogntiion

of any such claims.

The PLA could use its cyberwarfare capabilities to support military operations in three key areas.

First, cyber reconnaissance allows the PLA to collect technical and operational data for intelligence and potential operational planning for cyberattacks because the accesses and tactics, techniques, and procedures for cyber reconnaissance translate into those also necessary to conduct cyberattacks.

Second, the PLA could employ its cyberattack capabilities to establish information dominance in the early stages of a conflict to constrain an adversary’s actions or slow mobilization and deployment by targeting network-based C2, C4ISR, logistics, and commercial activities.

Third, cyberwarfare capabilities can serve as a force multiplier when coupled with conventional capabilities during a conflict. PLA military writings detail the effectiveness of information operations and cyberwarfare in modern conflicts, and advocate targeting an adversary’s C2 and logistics networks to affect the adversary’s ability to operate during the early stages of conflict

One authoritative source identifies an adversary’s C2 system as “the heart of information collection, control, and application on the battlefield. It is also the nerve center of the entire battlefield.”27

China’s cyberwarfare could also focus on targeting links and nodes in an adversary’s mobility system and identifying operational vulnerabilities in the mobilization and deployment phase.

The PLA also plays a role in cyber theft. In May 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted five PLA officers on charges of hacking into the networks of U.S. companies for commercial gain.

Beijing maintains that the Chinese government and military do not engage in cyber-espionage and that the United States fabricated the charges.28,29

China’s space launch fleet19,20,21.

China’s space launch fleet19,20,21.

— Denial and Deception —

The PLA uses military deception to reduce the effectiveness of adversaries’ reconnaissance and to deceive adversaries about the PLA’s warfighting intentions, actions, or major targets.30

PLA tradition emphasizes deception and psychological manipulation to create asymmetric advantages and enable surprise.

The PLA has a longstanding doctrine for deception, and claims that it regularly practices deception during training.

PLA sources describe military deception as a form of combat support, on par with ISR, meteorological support, missile calculation, engineering, and logistic support.

Denial and deception activities include:31

• Concealing and camouflaging.

• Blending false or misleading military movements with actual deployments and war preparations.

• Employing counter-reconnaissance: understanding and evading, jamming, or destroying the whole spectrum of enemy reconnaissance activities against PLA units and facilities.

• Using deceptive maneuvers, psychological ploys, and unorthodox schemes to deceive, confuse, or otherwise manipulate an adversary into a militarily disadvantageous position.32

Skillfully employed, deception can paralyze an enemy force and achieve decisive results. Options range from no-warning strikes, violent multi-axis strikes, and envelopment to a less ambitious attempt to confuse the adversary regarding the exact timing, nature, direction, or scope of a PLA operation.33,34

The complete DIA China Military Power report is available at: www.dia.mil/Military-Power-Publications

References

1Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017, Office of the Secretary of Defense; May 2017.

2Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017, Office of the Secretary of Defense; May 2017.

3Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017, Office of the Secretary of Defense; May 2017.

4Harvey, Brian, China in Space: The Great Leap Forward; 2013; Springer Science + Business Media; New York.

5Report; Stokes, Mark A. and Dean Cheng; Project 2049 Institute for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission; China’s Evolving Space Capabilities: Implications for U.S. Interests; 26 April 2012; http://project2049.net/documents/ uscc_china-space-program-report_april-2012.pdf.

6Report; Stokes, Mark A. and Dean Cheng; Project 2049 Institute for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission; China’s Evolving Space Capabilities: Implications for U.S. Interests; 26 April 2012; http://project2049.net/documents/ uscc_china-space-program-report_april-2012.pdf.

7White Paper; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China; China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System; June 2016; http://www.scio.gov.cn/zxbd/wz/ Document/1480433/1480433.htm.

8White Paper; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China; China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System; June 2016; http://www.scio.gov.cn/zxbd/wz/ Document/1480433/1480433.htm.

9Internet; Xinhua; China To Launch 30 Beidou Navigation Satellites In Next 5 Years; 19 May 2016; http://english.cas.cn/ newsroom/china_research/201605/t20160523_163363.shtml.

10Report; Stokes, Mark A. and Dean Cheng; Project 2049 Institute for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission; China’s Evolving Space Capabilities: Implications for U.S. Interests; 26 April 2012; http://project2049.net/documents/ uscc_china-space-program-report_april-2012.pdf.

11World Meteorological Organization; Satellite Status; accessed 17 October 2016; www.wmo.ing/pages/prog/sat/ satellitestatus.php.

12Annual Report to Congress; Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017; Office of the Secretary of Defense; May 2017.

13Peng Guangqian, Yao Youzhi, eds; 2001; Science of Strategy. 132 Li Bingyan, 27 Jan 2016; Beijing Guangming Ribao: General Trend of the Worldwide Revolution in Military Affairs and the Form of Future War.

14China Manned Space Engineering Office Website; Space Station Project Development Progress; 23 April 2016; http://www.cmse.gov.cn/uploadfile/news/uploadfile/ 201604/20160427104809225.pdf.

15Internet; Xinhua; Chang-E 5 To Launch Sometime in 2017 -- China’s Latest Secret Lunar Exploration Project Uncovered; 1 March 2014; http://news.xinhuanet.com/tech/2014- 03/01/c_119562037.htm.

16Xinhua: China To Land On Dark Side Of Moon In 2018; 14 January 2016; http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/ 2016-01/15/c_135010577.htm.

17Internet, NASASpaceFlight, Chang’e-5 Lunar Sample Return, CZ-5 - Wenchang - NET 2017, http://forum.nasaspaceflight. com/index.php?action=dlattach;topic=33431.0;attach= 1440126, Accessed 28 July 2017.

18Report; Stokes, Mark A. and Dean Cheng; Project 2049 Institute for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission; China’s Evolving Space Capabilities: Implications for U.S. Interests; 26 April 2012; http://project2049.net/documents/ uscc_china-space-program-report_april-2012.pdf.

19Briefing; Zhou, Yuanying; China Great Wall Industry Corporation; China’s Space Industry: Achievement, Future Planning and International Cooperation; presented by Zhou Yuanying for China Great Wall Industry Corporation at the 4th International Space Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania 18 Sept. 2012; updated 27 Sept. 2013.

20China Space Flight; Chinese Rocket service time; 12 March 2016; http://www.chinaspaceflight.com/rocket/China- launchers-timeline.html.

21Kevin Pollpeter and Kenneth Allen ed; 26 AUG 2015; DGI; The PLA as Organization: Reference Volume v2.0; pp 401.; http://www.andrewerickson.com/2015/12/a-classic-reference- with-renewed-relevance-download-the-pla-as-organization- v2-0/.

22Joe McReynolds; 17 APR 2016; Jamestown Foundation China Brief; China’s Evolving Perspectives on Network Warfare: Lessons from the Science of Military Strategy; pp 6; https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-evolving-perspectives- on-network-warfare-lessons-from-the-science-of-military- strategy/.

23Lincoln Davidson; ‘China’s Strategic Support Force: The New Home of the PLA’s Cyber Operations?’; CFR. org; Net Politics; January 20, 2016; http://blogs.cfr.org/ cyber/2016/01/20/chinas-strategic-support-force-the-newhome- of-the-plas-cyber-operations/.

24John Costello; ‘The Strategic Support Force: China’s Information Warfare Service’; The Jamestown Foundation; China Brief Vol. 16 Issue 3; February 8, 2016; https://jamestown. org/program/the-strategic-support-force-chinas-information- warfare-service/.

25John Costello; ‘China Finally Centralizes Its Space, Cyber, Information Forces’; TheDiplomat.com; January 20, 2016. 145 Peng Guangqian, Yao Youzhi, eds; 2001; Science of Strategy; pp 311.

26Department of Justice, “U.S. Charges Five Chinese Military Hackers for Cyber Espionage Against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization for Commercial Advantage;” May 19, 2014; URL: http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2014/May/14- ag-528.html.

27Lesley Wroughton, Michael Martina, “Cyber spying, maritime disputes loom large in U.S.-China talks,” Reuters, July 8, 2014, URL: https://www.reuters.com/article/ china-usa/cyber-spying-maritime-disputes-loom-large-in-u-schina- talks-idUSL4N0PJ0MT20140708.

28Zhang Yuliang (ed.), Science of Campaigns (National Defense University, Beijing, 2006; ISBN 7-5626-1407-0 ) p. 155-66.

29Zhang Yuliang (ed.), Science of Campaigns (National Defense University, Beijing, 2006; ISBN 7-5626-1407-0 ) p. 155-66.

30Zhang Xingye and Zhang Zhanli ed., Campaign Stratagems, (PLA National Defense University, Beijing, 2002),

p. 1-2, 26-8

31Zhang Yuliang (ed.), Science of Campaigns (National Defense University, Beijing, 2006; ISBN 7-5626-1407-0 ) p. 96-7.

32“Theories of the Initial Period of War” in Tiao Youzhi, ed., Theories of War and Strategy, PLA Press, Beijing, 2005 p. 564.

33Zhang Yuliang (ed.), Science of Campaigns (National Defense University, Beijing, 2006; ISBN 7-5626-1407-0 ) p. 96-7.

33“Theories of the Initial Period of War” in Tiao Youzhi, ed., Theories of War and Strategy, PLA Press, Beijing, 2005 p. 564.

The Director of National Intelligence — Daniel R. Coats — recently unveiling the 2019 National Intelligence Strategy (NIS) report.

Daniel R. Coats,

Director of National

Intelligence.

The NIS is the guiding strategy for the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) and will drive the strategic direction for the Nation’s 17 IC elements for the next four years.

The 2019 strategy is the fourth iteration for the NIS and seeks to make our nation more secure by driving the IC to be more integrated, agile, resilient, and innovative.

“This strategy is based on the core principle of seeking the truth and speaking the truth to our policymakers and the American people in order to protect our country,” said Director Coats. “As a Community, we must become more agile, build and leverage partnerships, and apply the most advanced technologies in pursuit of unmatched insights. The 2019 NIS provides a roadmap to achieve this end.”

The NIS is one of the most important documents for the IC, as it aligns IC efforts to the National Security Strategy, sets priorities and objectives, and focuses resources on current and future operational, acquisition, and capability development decisions.

Also, the NIS provides the IC with the opportunity to communicate those national priorities to the IC workforce, partners, oversight, customers, and fellow citizens.

The 2019 NIS focuses on:

• Integration — harnessing the full talent and tools of the IC by bringing the right information,

to the right people, at the correct time.

• Innovation — making the IC more agile by swiftly enabling the right people and leveraging the right technology and using them efficiently to advance the highest priorities.

• Partnerships — leveraging strong, unique, and valuable partnerships to support and enable national security outcomes.

• Transparency earning and upholding the trust and faith of the IC’s customers and the American people.

The NIS was developed in response to rapid advances made by our adversaries and the ODNI’s recognition that the IC needs to change to more effectively respond to those challenges.

In his 2019 NIS opening message, the DNI stated, “We face a significant challenge in the domestic and global environment; we must be ready to meet 21st century challenges and to recognize emerging threats and opportunities. To navigate today’s turbulent and complex strategic environment, we must do things differently.”

To guide the IC in facing these challenges, the NIS identifies and explains the IC’s objectives — both what the Community must accomplish (mission objectives) and what capabilities the Community must build in order to do so (enterprise objectives).

The seven mission objectives are...

1) strategic intelligence

2) anticipatory intelligence

3) current operations intelligence

4) cyber threat intelligence

5) counter-terrorism

6) counter-proliferation

7) counterintelligence and security.

The seven enterprise objectives are...

1) integrated mission management

2) integrated business management

3) people

4) innovation

5) information sharing and safeguarding

6) partnerships

7) privacy, civil liberties, and transparency.

“These objectives will allow the IC to continue the crucial work of supporting our senior policymakers, warfighters, and democracy while increasing transparency and protecting privacy and civil liberties,” said Director Coats. “Transparency will be our hallmark, and I cannot stress this enough - this is not a limitation on us. Transparency will make us stronger. It is the right thing to do, across the board. This is the reason we publish the NIS at the unclassified level.”

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence oversees the coordination and integration of the 17 federal organizations that make up the Intelligence Community (see the infographic on the following page).

The DNI sets the priorities for and manages the implementation of the National Intelligence Program, which is the IC’s budget.

Additionally, the DNI is the principal advisor to the President and the National Security Council on all intelligence issues related to national security.

In this report, within the Strategic Environment section, the authors note:

Traditional adversaries will continue attempts to gain and assert influence, taking advantage of changing conditions in the international environment—including the weakening of the post-WWII international order and dominance of Western democratic ideals, increasingly isolationist tendencies in the West, and shifts in the global economy.

These adversaries pose challenges within traditional, non-traditional, hybrid, and asymmetric military, economic, and political spheres.

Russian efforts to increase its influence and authority are likely to continue and may conflict with U.S. goals and priorities in multiple regions.

Chinese military modernization and continued pursuit of economic and territorial predominance in the Pacific region and beyond remain a concern, though opportunities exist to work with Beijing on issues of mutual concern, such as North Korean aggression and continued pursuit of nuclear and ballistic missile technology.

Despite its 2015 commitment to a peaceful nuclear program, Iran’s pursuit of more advanced missile and military capabilities and continued support for terrorist groups, militants, and other U.S. opponents will continue to threaten U.S. interests.

Multiple adversaries continue to pursue capabilities to inflict potentially catastrophic damage to U.S. interests through the acquisition and use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), which includes biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons. In addition to these familiar threats, our adversaries are increasingly leveraging rapid advances in technology to pose new and evolving threats — particularly in the realm of space, cyberspace, computing, and other emerging, disruptive technologies.

Technological advances will enable a wider range of actors to acquire sophisticated capabilities that were previously available only to well-resourced states.

No longer a solely U.S. domain, the democratization of space poses significant challenges for the United States and the IC. Adversaries are increasing their presence in this domain with plans to reach or exceed parity in some areas.

For example, Russia and China will continue to pursue a full range of anti-satellite weapons as a means to reduce U.S. military effectiveness and overall security.

Increasing commercialization of space now provides capabilities that were once limited to global powers to anyone that can afford to buy them.

Many aspects of modern society — to include our ability to conduct military operations — rely on our access to and equipment in space. Cyber threats are already challenging public confidence in our global institutions, governance, and norms, while imposing numerous economic costs domestically and globally.

As the cyber capabilities of our adversaries grow, they will pose increasing threats to U.S. security, including critical infrastructure, public health and safety, economic prosperity, and stability.

When analyzing cyber threats, the National Intelligence Agency reports that Detect and understand cyber threats from state and non-state actors engaged in malicious cyber activity to inform and enable national security decision making, cybersecurity, and the full range of response activities.

Despite growing awareness of cyber threats and improving cyber defenses, nearly all information, communication networks, and systems will be at risk for years to come.

Our adversaries are becoming more adept at using cyberspace capabilities to threaten our interests and advance their own strategic and economic objectives.

Cyber threats will pose an increasing risk to public health, safety, and prosperity as information technologies are integrated into critical infrastructure, vital national networks, and consumer devices.

The IC must continue to grow its intelligence capabilities to meet these evolving cyber threats as a part of a comprehensive cyber posture positioning the Nation for strategic and tactical response.

Daniel Coats introduced this report with an opening statement...

“As the Director of National Intelligence, I am fortunate to lead an Intelligence Community (IC) composed of the best and brightest professionals who have committed their careers and their lives to protecting our national security. The IC is a 24/7/365 organization, scanning the globe and delivering the most distinctive, timely insights with clarity, objectivity, and independence to advance our national security, economic strength, and technological superiority.

“This, the fourth iteration of the National Intelligence Strategy (NIS), is our guide for the next four years to better serve the needs of our customers, to help them make informed decisions on national security issues, and to ultimately keep our Nation safe.

“The NIS is designed to advance our mission and align our objectives with national strategies, and it provides an opportunity to communicate national priority objectives to our workforce, partners, oversight, customers, and also to our fellow citizens.

“We face significant changes in the domestic and global environment; we must be ready to meet 21st century challenges and to recognize emerging threats and opportunities. To navigate today’s turbulent and complex strategic environment, we must do things differently. This means we must:

• Increase integration and coordination of our intelligence activities to achieve best effect and value in executing

our mission,

• Bolster innovation to constantly improve our work,

• Better leverage strong, unique, and valuable partnerships to support and enable national security outcomes, and

• Increase transparency while protecting national security information to enhance accountability and public trust.

“This National Intelligence Strategy increases emphasis in these areas. It better integrates counterintelligence and security, better focuses the IC on addressing cyber threats, and sets clear direction on privacy, civil liberties and transparency.

“We have crucial work before us. Our customers depend on us to help them to make wise national security decisions, and Americans count on us to help protect the Nation, all while protecting their privacy and civil liberties.

“We must provide the best intelligence possible to support these objectives; doing so is a collective responsibility of all of our dedicated IC professionals and, together with our partners, we can realize our vision.

“Our ongoing goal is to continue to be the very best intelligence community in the world. Thank you for your service and for bringing your talent and commitment to the work of keeping our Nation safe each and every day.”