When a country goes to war, instruction is passed from the highest serving public minister, to government, and then to a unit or department responsible for preparing for the ensuing engagement.

Back in 2001 in the United Kingdom (UK), it was The Permanent Joint Headquarters (PJHQ) and the Chief of Staff (Operations) who were responsible for the planning and execution of operations. Requirements are divided between nine divisions—J1 through J9—who oversaw requirements ranging from personnel (J1) through to logistics (J4) and communications (J6).

Being a communications specialist, I attended/participated as part of the J6 community and was involved in preparations for the British participation of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan.

Each J division has an important role to play and none more so than J4, responsible for logistics. Preparing for operations; organizing and transporting everything required to engage is a huge undertaking. Getting logistics correct the first time is vital from a monetary perspective, but even more important from an operational one.

Traditionally, some militaries have used commercial container tracking technology to manage logistics; radio frequency identification (RFID) tags attached to assets enable teams to track them in controlled areas such as ports or storage depots, as longs as consignments stay within the RF bubble, piping the information back to a central logistics system. Once the cargo moves outside of the radio bubble, tracking systems typically rely on GSM/GPRS and send geotag data and status as, and when, they enter areas of coverage. This could mean days without updates as ships en-route to war zones cross vast distances carrying thousands of ISO containers full of equipment.

However, military logistics has traditionally been problematic. The distances involved, often through austere environments and the complexity, can cause delays—this is an operational headache.

I witnessed many situations in Joint Helicopter Command where critical helicopter parts either got delayed or, worse still, were lost. This had serious operational consequences in providing air capability. We had limited real-time consignment information in those days; therefore, the risk and operational effect was difficult to evaluate—there were no life or death situations, but this may not always be the case.

And that wasn’t in a new territory, that was a war zone in which we’d had a ten year presence and logistics had been set up and running for some time. With little real-time visibility into the location and status of cargo, militaries struggle to run efficient operations.

Once a conflict is over and a military force is faced with shipping everything back home, they typically face a different problem—interference. Huge container shipping yards are often guarded by local skeleton security teams who have no chance of effectively patrolling and securing thousands of ISO containers. Even worse, it may be in their financial best interests to let third parties into the yard to open crates and investigate their contents.

As far as the military is concerned, its last good intelligence indicates the container hasn’t moved and is where it should be, so all is good. The first they know of any foul play is when they receive the container, open it up, and find the multi-million dollar Apache engine on the manifest has been replaced with sand and rocks. Sounds too ridiculous to be true, but it happens.

And it’s not just theft that needs to be addressed. Insurgents will look for any opportunity available to attack an allied base—tampering with cargo and concealing an incendiary device within an ISO container for example, is a way into a secure compound and could have disastrous consequences once it reaches its destination.

The incumbent military force you’re working alongside in a foreign territory should also be factored into logistics planning. Maybe a local security outfit decides that if 90 percent of the equipment reaches its final destination, then that’ll be good enough. They are used to working alongside different allies on a regular basis and will naturally look out for themselves. That interference is costly from a monetary perspective and, once again, could have severe operational ramifications.

Track24 Defence Shadow Device

Effective and secure consignment tracking is, therefore, an essential operational requirement for modern day militaries. Unfortunately it’s not as easy as procuring tracking technology straight from the commercial sector—systems typically fall short in two main areas: real-time intelligence and security.

Conventional RFID and GSM/GPRS tracking devices attached to ISO containers report on location and speed when in areas of coverage. But that intelligence is of limited value if it is not in real time or you don’t know the status of the cargo inside the ISO.

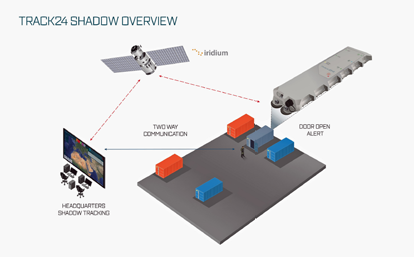

Instead, militaries are turning to advances such as secure M2M satellite, ZigBee mess networks and sensors to provide beyond line-of-sight data visualization for logistical intelligence. In the instance of an ISO container, sensors can report on the temperature, levels of light, door open/closed or movement within the container. This information is then encrypted and sent via commercial satellite back to HQ, where it becomes part of the overall common operational picture.

Military grade consignment tracking technology also enables users to change the configuration of the sensors with firmware updates that are managed from the HQ. These are not maintenance patches like the ones you’d periodically download on your smartphone, but instead live telemetry updates to solve operational problems—for example, thresholds in a container with refrigeration units can be configured to provide

real-time alerting if temperatures rise, this provides valuable information about a possible faulty cooling unit.

Another critical feature is the ability to send the sensor within the container a geofence or map area that triggers an alert if the container is moved outside of this area: this updates the J4 operations staff of consignment movement in real-time. This feature is also used as way points for journey management. With live firmware updates configurable anywhere in the world, these geofences can be updated at any time and anywhere.

Shadow Device Attached to a container

However, commercial solutions often lack the military grade command and control backend required to run an effective operation. The device itself is only ever part of an overall blue force tracking solution giving commanders the opportunity to integrate logistics intelligence with information from other devices assigned to assets in the field.

Seamless compatibility is required to run efficient operations; being able to align assets with cargo is essential, especially in the face of insurgent disruption. This could be as simple as setting up geofences to alert nearest responders if consignments stray off course, or messaging and coordinating friendly forces to accompany convoys transporting cargo as they move through high risk areas.

Commercial devices also fall short on security. The most common ones don’t encrypt their signals before transmission which leaves them open to interception. In a physical sense they also aren’t that secure as they are attached to the outside of the cargo itself—instead, militaries need covert solutions designed to avoid detection, therefore reducing the chance of interference. In the instance when the device is discovered or compromised or detached, the mess network capability allows other devices in the local area to automatically send alerting signals to predetermined assets.

Ultimately, the benefits of Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) solutions are affordability, ease-of-use and allied compatibility (if you’re part of an engagement with multiple partner states you need to command and control all consignments at the same time regardless of origin or destination). In order to ensure cost savings as well as operational efficiency it’s necessary to consider the satellite capability, telemetry, security and overall solution the device sits within, otherwise it’s just a dot on a screen.

Giles Peeters commenced his military communications career in the UK’s Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1989. He worked in the MoD’s Defence Communications Security Agency (DCSA) as operations officer and procurement manager in the Satellite Service Delivery team, before moving to the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) Cheltenham in 2001. From 2004 to 2007 Peeters’ significant expertise in commercial satellite communications proved invaluable in Iraq and Afghanistan as he provided front line tactical communication and deployment capability for Joint Helicopter Command. Peeters’ final rank was RAF Squadron Leader. In 2007 Peeters moved to the private sector and provided blue force tracking to NATO and the EU. Now Defence Sector Director at Track24 Defence, Peeters is the driving force behind the company’s commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS), beyond line-of-sight, blue force tracking solution, Situational Command & Control (SCC) TITAN.