Airborne ISR — the use of manned and unmanned aerial systems (UAS) for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance — continues to evolve to address current and future challenges facing America’s military.

Those challenges include more advanced and sophisticated adversaries capable of disrupting the near impunity our UAS resources currently have in the skies, and a much more contested environment where UAS survivability

isn’t guaranteed.

At the same time, the military is actively looking to use new technologies, making troops better informed and aware in the field. ISR and communications solutions in forward operating bases (FOBs) ensure the warfighter has real-time situational awareness. However, when the soldier leaves the FOB, current technology does not allow for the same level of situational awareness to go with them.

These challenges — and the steps the military is taking to overcome them — were expertly detailed in a recent article in National Defense magazine (www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2017/6/14/special-ops-community-eyeing-new-drone-technology). Perhaps the most notable step detailed in the article is to achieve Group 4 UAS capability on a Group 3 size platform.

According to Mike Fieldson, airborne ISR division chief at SOCOM’s program executive office fixed wing, this means a move away from Group 4 and Group 5 drones, which weigh more than 1,320 pounds, and toward a smaller and lighter UAS in Group 1 through Group 3.

As Mr. Fieldson put it, “The intent…is to take Group 4 and Group 5-type capabilities and push that down into a Group 1, Group 2, Group 3-type configuration.”

Shrinking America’s fleet of UAS resources can have multiple benefits for the military. Most Group 3 UAS don’t require a runway, lowering their signature in a given area. They require less power to operate. They’re significantly less expensive. In addition to this, their low cost and small size makes it more feasible to use multiple assets for each mission, greatly increasing resiliency through redundancy.

This plan to go smaller and proliferate UAS resources was shared in the article by Lieutenant General Kenneth Tovo, commander of Army Special Operations Command, who said, “The large [UAVs] that we’re relying on now perhaps could be replaced by a multitude of essentially throwaway swarms of UAVs.”

This concept of creating swarms of smaller UAVs seems plausible enough — however, there are challenges. While moving to a smaller UAS isn’t limited by the platform, the biggest challenge to a Group 3 UAS is often overlooked — the antenna required for Beyond Line of Sight

(BLoS) operations.

The Incredible Shrinking Antenna

For UAS fleet resources to shrink in both size and weight, they’ll need all components to shrink as well. This includes the sensors and the antenna used to transmit data back to the personnel aggregating, analyzing and drawing actionable intelligence from the data.

To accomplish this, satellite hardware manufacturers — such as GetSat (getsat.com/) — are working feverishly on a new generation of advanced antennas. These antennas can sit flatter on surfaces to reduce drag and are more aerodynamic, and are smaller. The most exciting new antenna technologies are flat panel arrays and the “Holy Grail,” electronically steered aperture (ESA) antennas.

Hardware manufacturers are also working to develop a new generation of software-defined modems which are smaller and can be paired with new antenna designs to make the entire apparatus responsible for sending and receiving data more compact.

However, smaller antennas aren’t always the panacea. Yes, they cut down on size and weight and can help the military usher in an era of smaller UAS resources. But they give SATCOM providers nightmares and leave users wanting higher throughput.

Shrinking from the Spotlight

Small antennas mean problems for satellites, regardless of how sophisticated and advanced they become. The smaller an antenna is, the greater the opportunity for adjacent satellite interference to occur.

Although emerging commercial GEO SATCOM solutions are designed to be used with smaller antennas — such as those found on commercial aircraft — the military has been reticent to use them, mostly because commercial practices for these new technologies run counter to their critical requirements.

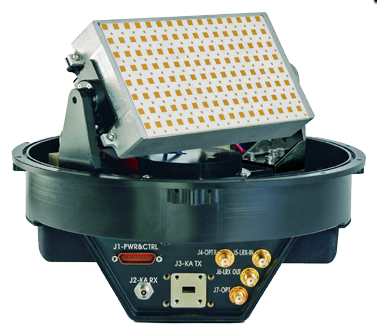

GetSat's Nano SAT, the smallest KA Band SOTM Terminal in the market. Photo courtesy of the company.

This means as the commercial SATCOM industry focuses investments on technologies necessary to meet the demands of the always connected commercial world, it does little to address the ISR requirements for smaller antennas required for the next, highly-coveted, Group 3 UAS class.

Luckily, two solutions could already be in space — MEO satellite constellations and GEO High throughput satellites (HTS). Unlike traditional wideband GEO satellites, these satellites use high-powered, concentrated spot beams that are easier for smaller antennas to access.

The preceding article is republished courtesy of The Government Satellite Report (GSR), produced by SES Government Services (ses-gs.com/govsat/)

Paul Hopkins is the Senior Director for Government Programs at SES Government Solutions. Prior to beginning his career with SES GS, Paul had a long career with the United States military, where he served in multiple positions, including PM of Special Programs at U.S. SOCOM and Special Assistant to the Vice Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.