In 2012 General Ellen Pawlikowsi, then Commander of the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center, foretold of the adoption of new military satellite design and acquisition strategies in order to “affordably provide resilient space capabilities . . . as mission needs evolve.”1

In the five years since that statement, commercial satellites have been redefined by a flood of investment in commercial constellation programs — raising the question whether this “new space” supply chain can meet the vision of affordability and resiliency for future military missions.

General Pawlikowski argued for two key shifts in military acquisition strategy. First, she endorsed a hosted-payload acquisition strategy leveraging emerging commercial bus and rideshare opportunities as opposed to the traditional dedicated military satellite/launch vehicle paradigm.

Secondly, she pleaded for a move away from aggregated, highly centralized and long-life satellite architectures in deference to distributed satellite constellations with shorter lifespans to encourage more frequent technology upgrades. Both strategies are now well within the reach of the U.S. Military because of substantial commercial investments over the past five years.

Coincidentally in 2012, Greg Wyler founded OneWeb to provide internet access to anyone, anywhere on the planet. Since then, his vision has grown into a multi-billion-dollar corporate venture that will launch its first satellites in 2018. If all goes as planned, these inaugural flights will prove the viability of global Internet from space and the profitability of delivering it using 900 satellites with individual design lifespans of only three to four years.

Closing the business case has forced OneWeb to demand unprecedented low unit prices from their supply chain. Meeting those prices while staying in business has forced their supply chain to develop innovative component designs that are simple, can be produced with minimal touch labor, and can be flight qualified using standards more akin to the commercial aviation industry like lot-acceptance testing.

Moreover, OneWeb and their competitors, such as SpaceX, are finding the need to bend management norms for flight hardware development. Creative cost-sharing and infrastructure financing are proving as important to overall program success as the traditional earned-value-management obligations to cost, schedule, and risk.

In order to enforce a different culture, SpaceX initially staffed their satellite division with several dozen ex-software engineers and program managers for whom the build-test-learn-revise methods are the only way to design a system.

Just as Toyota proved to the automotive industry in the 1980’s, today’s mega-satellite-constellation industry is learning that affordability and resiliency is deeply rooted in a healthy and agile supply chain. Two-way transparency is becoming as important to the B2B relationship as the ubiquitous non-disclosure agreement, and the dialog is revealing a very different business case for component providers.

Gone are the days of maintaining a standing engineering army that feeds on design change orders as the schedule pushes right. Becoming a “bonded” supplier to the likes of OneWeb or SpaceX requires a passion for delivering on time, and a recognition that the business long game will be found in the recurring orders for second, third, and fourth generation constellations launched by these companies . . . assuming their first generation works.

More importantly than even slashing component prices and development times, this “new space” supply chain is being challenged to produce component designs that can deliver unprecedented performance to vanishingly small satellite platforms — because satellite size is really the key driver of constellation cost.

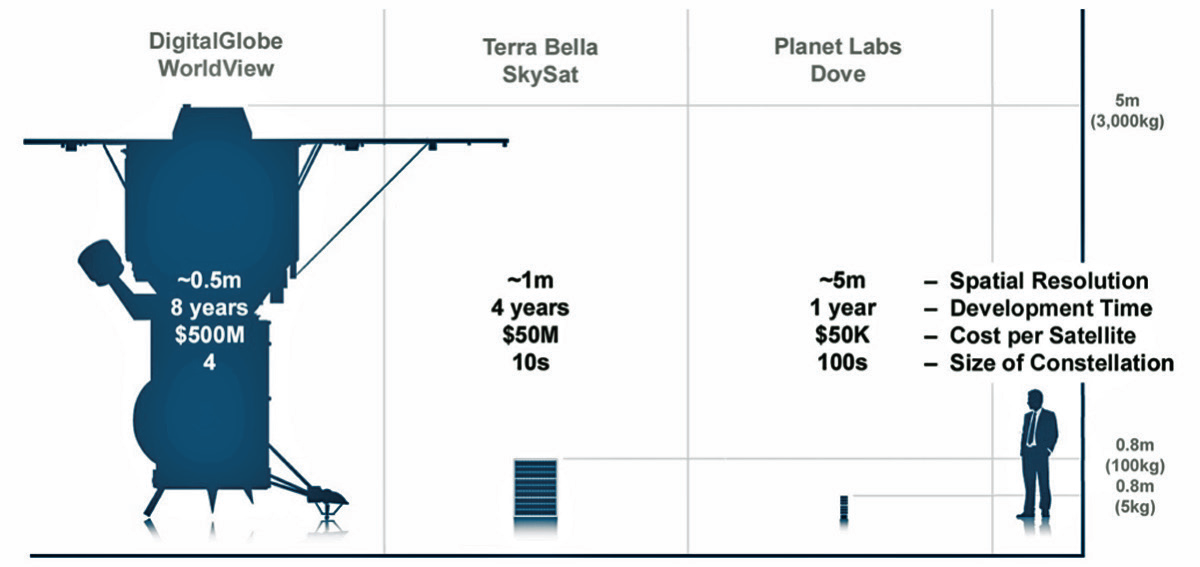

Ten years ago, DigitalGlobe (now a subsidiary of MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, MDA) launched their first WorldView satellite — a 3,000 kg satellite — at a cost of ~$500 million and after an eight year development cycle. Since then, the DigitalGlobe constellation has grown to four satellites — all of similar size and cost — to provide customers with ubiquitous imaging of the Earth’s surface to ~0.5 meter spatial resolution.

Meanwhile DigitalGlobe’s market share has slowly eroded by more recent entrants into the global imaging market: Terra Bella, which was founded in 2009 and is now a division of Planet Labs, and Planet Labs itself, which was founded in 2010.

Image is courtesy of the Science and Technology Policy Institute2.

Unlike DigitalGlobe's corporate roots in the DoD’s Strategic Defense Initiative of the 1990’s, these recent start-ups are rooted in Silicon Valley business tactics and have launched dramatically smaller and more affordable satellites for their constellations — deciding to sacrifice modestly on spatial resolution in order to deliver a more sustainable data product at a more affordable price point.

The question then remains: how can this emergent “new space” supply chain be a resource to the U.S. military and its top-tier suppliers and a means to achieve General Pawlikowski’s vision of affordability and resiliency?

In 2009, the Australian Defense Force (ADF) announced a novel commercial/military agreement for development and launch of a military UHF payload on an Intelsat commercial satellite.3 The agreement led to “significant cost and schedule savings compared to a dedicated [military] satellite,” and provided “a good example of the types of reforms required to ensure the most efficient use of Government finances.” (Press release by the Minister of Defense, Australia, May 2009)

The ADF/Intelsat business partnership was consummated in 2012 with the successful launch of the UHF hosted payload with an advertised savings of $150 million and roughly four years of development time to the Australian Defense Force — an event that may have, at least partially, motivated General Pawlikowski's plea the same year for a new acquisition strategy to be adopted in the U.S. military.

This change in acquisition mindset is now possible. However, for the U.S. Military to meet the vision of affordability and resiliency as foretold by General Pawlikowski, it must cash in on the rapidly expanding commercial ride share opportunities, and embrace the move to smaller satellite platforms and the “new space” management norms that are being established by the mega-satellite-constellation industry and its growing and agile supply chain.

www.roccor.com

References

1Ellen Pawlikowski, Gen., USAF, et al., “Space: Disruptive Challenges, New Opportunities, and New Strategies,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, Spring 2012

2Bhavya Lal, et al., “Global Trends in Space Volume 2: Trends by Subsector and Factors that Could Disrupt Them,” IDA Paper P-5242, Vol. 2, Science and Technology Policy Institute, June 2015.

3Don Brown, “2012: A Milestone in the History of Military Satellite Communications on Commercial Satellites,” APSCC Quarterly Newsletter, Fourth Quarter 2012

Doug Campbell is the CEO of Roccor, a world leader in low cost composite deployment systems and thermal management devices for commercial and military satellites. Campbell is a serial entrepreneur with more than 15 years of experience in technology commercialization within the aerospace and clean technology sectors.

He holds an M.S. in Civil/Structural Engineering from the University of New Mexico and began his career as a research assistant at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Space Vehicles Directorate, Kirtland AFB, New Mexico.