Edited By Dan Makinster, Technical Military Advisor, SatNews

Preparing For The Unexpected In Space

By Nancy Rey Nolting, Marketing Programs Mgr., Intelsat General Corp.

There is a common thread through all of the speculation—informed and otherwise—about future conflicts on the global stage: Expect the unexpected.

It’s an axiom built upon lessons learned over centuries of conflict, but it leaves an important question: How do you prepare for

the unexpected?

The question was asked and answered by Skot Butler, Intelsat General’s Vice President for Satellite Networks and Space Services, who presented at the 17th annual Global MilSatCom symposium in London last November.

The commercial satellite community has been preparing for the unexpected globally for years in partnership with the military. Examples include the Skynet fleet public-private partnership in the UK, the SES-Luxembourg joint venture to build and operate a commercial satellite with military frequencies, and Intelsat’s UHF payload for the Australian Defence Force.

Cases are being forged in the U.S., where there is a long history of leasing commercial SATCOM for military and government needs. Conversations are ongoing about the commercialization of WGS flight operations, part or all of the Air Force Satellite Control Network and even the future Wideband space system itself. In the conversations, there are challenges.

Gen. John Hyten, who heads Air Force Space Command, said on December 8, 2015, that he is encouraging the use of “resilient capacity” when planning future space architectures. In that, he wants an analysis of how space capabilities operate through an integrated, combined, and joint threat to continue to provide support to the warfighter. That analysis will have to include commercial capability that aligns with

DoD needs.

IGC’s Skott Butler.

“It’s up to our community of operators, bus and payload manufacturers, cyber and Information Assurance experts … in partnership with those in government who are responsible for the next-generation architecture of military satellite communications, to ensure that this transition—whatever its final form may be—ultimately delivers the commanders and warfighters the rapid, secure, and resilient communications capabilities upon which modern warfare so heavily relies,” Butler said.

To do so, commercial satellite providers have some inherent advantages:

Speed of fielding: With an emphasis on technology development, coupled with a future of reusable rockets, domestic engines and rapid range turns, and with a movement toward modular satellite bus design, industry is trending toward a just-in-time COMSAT model. It’s a game-changer in supporting a troop surge or any military response.

Rapid technology adoption: The commercial satellite industry needs to be designed into future military satellite architectures to fully realize the potential of a commercial-military partnership. Commercial is now moving to meet the capabilities the military expects of its own systems. As an example, by 2020, commercial satellites will have security features, such as nulling and beam forming, and laser and software defined payloads as standard fare.

Resiliency through distribution: a combination of commercially hosted payloads, small free-flyers and traditional capacity leases may be required because a one-size-fits-all solution is neither practical nor usually possible for the complex needs of the military. Being open to the variety of architectures that commercial can provide can increase mission security.

As an example of the innovation more commercial involvement could bring, the 10th Wideband Global SATCOM (WGS) satellite is scheduled to become fully operationally capable (FOC) in 2017, more than a decade after the first went aloft and at least 15 years after the design phase.

“A program that will take close to two decades from design to FOC naturally carries the burden of outdated technology and capacity limitations, which a capability built on a commercial model would not,” Butler said.

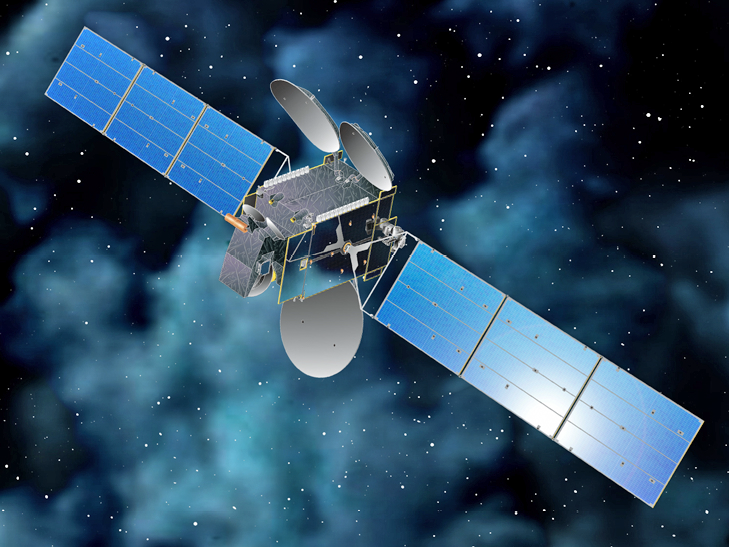

Intelsat’s EpicNG, the upcoming high-throughput satellite network, is built on the same bus as WGS and the first of at least seven will be launched next year on a standard three-year commercial timeline.

Considering the rapid development of technology and of the capabilities of our emerging global space competitors, as well as the unpredictable nature of conflict, it’s clear that commercializing wideband communications is an idea whose time has come.

As important, this year has shown that the commercial sector provides value added to terrestrial satellite operations, with the military looking toward it for “smarter use of scarce dollars,” Butler said. He offered an example of the seven ground infrastructure sites of the Air Force Satellite Control Network sites and their looming modernization and operations bills.

“Meanwhile,” he added, “commercial ground segment operators have existing assets and facilities with available capacity and a range of customer market segments over which they can spread their costs, allowing continuous investment in infrastructure, hardware and software to maximize efficiency and minimize the highest risk element—man in the loop.”

That brought up security. DoD has for several years required satellite bandwidth and services providers to meet a set of some 200 security controls.

“Long before this requirement was levied on us, Intelsat saw the criticality of protecting our networks and began a defense in depth program that focuses on our three pillars of information security: confidentiality, availability, integrity,” Butler said.

The pathway toward coping with an unexpected future starts at the beginning of military satellite programs. The commercial sector must be involved.

“I don’t believe we can identify every possible contingency that might arise during the life of this architecture,” Butler said, “but if we have a resilient, diversified design, we should be well positioned to adapt to these unknowns.”

Acquisition Woes Delay DoD Technology Upgrades

By Matthew Bearzotti, Manager, Government Affairs, Intelsat General Corp.

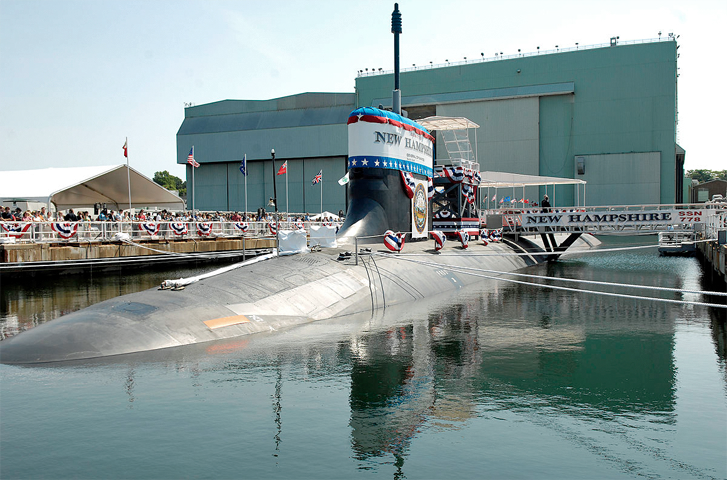

In October 25, 2008, the Navy commissioned the USS New Hampshire, a Virginia-class submarine, eight months ahead of schedule and $54 million under budget for the Navy by prime contractor General Dynamics.

This example shows that by adapting techniques and products from the commercial sector, the Pentagon can successfully field technology quickly under its existing weapons acquisition system.

Unfortunately the New Hampshire is the exception, not the rule, witnesses told the Senate Armed Services Committee on December 1, 2015.

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who chairs the committee, pointed to several attempts at reform that have failed to change a system that is risk averse and less open to commercial solutions than it was three decades ago, according to an account of the hearing in Defense Systems.

An Air Force general echoed McCain’s criticism when speaking at a December 15 National Contract Managers Association event

in Washington.

“We’ve got some risk averse folks out there who don’t really understand the commercial side,” said Maj. Gen. Casey Blake, the Air Force’s deputy assistant secretary for contracting, according to an article in insidedefense.com.

The difference between defense and commercial technology development is why, when the final Wideband Global SATCOM (WGS) satellite is launched in 2017, a decade and a half will have lapsed from system design to implementation.

That contrasts with the expected six-year commercial timeline from design to launch of Intelsat General’s EpicNG High Throughput Satellite (HTS) platform, with the first satellite slated for launch in January 2016.

The U.S.S. New Hampshire.

Among 180,000 pages of military procurement regulations is a section called “lowest price/technically acceptable” or LPTA.

While valid for some government buys, LPTA fosters longer timelines that support the way the Air Force built WGS, as opposed to a quicker, more technically up to date system like that of Intelsat EpicNG.

By its very nature, LPTA does not foster innovation, and it does nothing to prevent development delays and cost overruns.

Ben FitzGerald, director of the Center for the New American Security’s Technology and National Security Program, told the Senate Armed Services Committee that the Pentagon continues to cling to a Cold War acquisitions model, which makes partnering less compelling to the private sector.

A 180-degree technology switch has developed. Where once DoD drove innovation, the military increasingly adapts technology developed commercially.

“We are managing around the system,” FitzGerald testified. “I get incredibly frustrated when the answer is always ‘change the system,’ and the thing we can’t do is change the system.”

Still, Congress tries to change the system while it also worries over technology gaps that are sending customers to France to buy night-vision equipment and to China to overcome U.S. import/export issues.

Artistic rendition of the Intelsat 34 HTS satellite.

The hope is that Congressional attempts can make a difference and start to resolve this problem.

The Virginia-class submarine success shows that the DoD can do better. The United States must do better if it is to address the challenge of new adversaries in space.

The difference in development time to implementation of the WGS versus the development of more modern commercial satellites is an example of the best way forward.

Editor’s note:

All of these articles are republished with permission of Intelsat General Corporation and their SatCom Frontier blog.

The SatCom Frontier blog may be accessed at intelsatgeneral.com/management-team/satcom-frontier/

Space Command Should Be A Dynamic Force

By Rory Welch, Director, Business Development, Intelsat General Corp.

General John Hyten bridles at the perception of his Air Force Space Command being comprised of technicians in a 9-to-5 office environment reacting to threats thousands of miles above Earth.

It’s a perception he wants to correct, Hyten told the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies “Space Power for the Warfighter” breakfast seminar, on December 8

in Washington.

Space Command should be proactive, and space is no longer tranquil. It’s a contested environment, the Commander said in a speech entitled “My First Year in Perspective: What Did We Get Done?”

Among other critical space missions, Space Command is challenged to provide and maintain the Global Positioning System capabilities warfighters use to target and time weapons and to navigate on the battlefield. The command also combines military and commercial satellite assets to give those branches the ISR and communications needed to win today’s wars.

Where once there was a race to the moon, the space race today is to maintain the technological superiority and freedom of access to space that the U.S. enjoys in preparation for the wars of tomorrow. That edge helps in coping with satellite interference, both intended and incidental, as well as with looming kinetic threats to our space assets from China and Russia that could turn space into a debris-infested wasteland.

Hyten contrasted the potential aftermath of war on the ground with that in space. On the ground, he said, rebuilding a bombed area can return it to its previous state of usefulness in a short time. But geosynchronous orbit is the most valuable real estate in space, and debris there can render it useless for centuries.

As part of maintaining that edge, Hyten wants control of the seven satellite systems operated by Space Command to be fused into a single enterprise. The new enterprise would knock down barriers to communication that were part of the stove-piped control system approach, and it would also facilitate missions that can take advantage of the capabilities of different mission systems.

USAF General John Hyten, Commander, Air Force Space Command. Photo is courtesy of Space Foundation.

Key to the future is also the concept of the “Space Mission Force” (SMF). Training of the first SMF will begin next spring at Schriever Air Force Base, with airmen rotating between dedicated duty in satellite and ground systems operations, and then rotating back for intensive training and certification. This links closer to how other arms of the Air Force conduct business.

He also highlighted the role for the commercial sector in the new enterprise, which has been discussed extensively over the past year. One idea advanced is for commercialization of certain satellite flight operations missions freeing the uniformed SMF personnel to plan and execute more critical missions, react to threats, monitor satellites and stay ahead of a rapidly changing potential battlefield in space.

The SMF represents a change in Air Force thinking, Hyten said. The service also should change the way it thinks about space system plans and acquisitions. Threats to assets should be factored into equations predicting their lifetimes.

He highlighted that a recent Analysis of Alternatives recommended maintaining the existing architecture with few changes. This is not acceptable in the new contested and congested space.

The status quo is not resilient, Hyten said, and the use of outdated metrics is no longer a valid path toward maintaining space superiority. This is a message the Air Force needs to convey to those who provide funding to secure that future, including Pentagon planners and Congress.

Determining threats is part of Space Command’s interaction with the Intelligence Community and other service branches at the Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC). Early identification of a threat can allow Space Command minutes (for satellites in low Earth orbit) or hours (in GEO) to react with capabilities already built into space assets.

Also, Space Command is developing and refining Tactics, Techniques and Procedures for using those capabilities and doing realistic testing of these at the newly created Joint Interagency Combined Space Operations Center (JICSpOC).

Other branches are starting to include Space Command in planning operations. Such cooperation is fostering an environment in which the Intelligence Community, Space Command and industry can better develop a space architecture to meet the demands of a dynamic future.